Palliative care not yet a routine part of full cancer experience

New report reinforces the need for integrating palliative care immediately following a cancer diagnosis

September 18, 2017

(TORONTO) – The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer has released a report on the state of palliative and end-of-life care for patients with cancer in Canada. The report finds that patients who could benefit from palliative care are not being identified, assessed and referred early enough in their cancer experience so that appropriate care can be part of treatment as soon as possible.

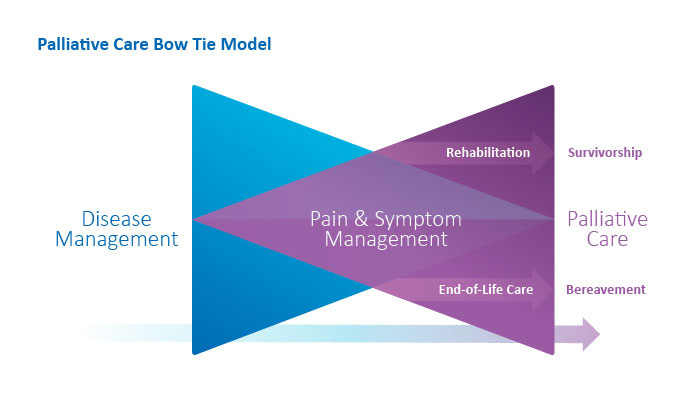

Evidence suggests earlier integration of palliative care has the potential to improve treatment outcomes and prolong survival.[1,2] (See the Bow Tie Model graphic below.) Evidence also reinforces that end-of-life care provided at home improves quality of life for people with cancer and reduces unnecessary and repeated hospital stays.

“We must redefine palliative care. This type of physical, psychosocial and spiritual support should not be so closely associated with end-of-life care, and should be incorporated soon after a cancer diagnosis,” said Dr. Deborah Dudgeon, Senior Scientific Leader, Person-Centred Perspective at the Partnership. “The World Health Organization defines palliative care as ‘relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems.’ We need to start following this definition in our approach to cancer treatment.”

Palliative and End-of-Life Care: A Cancer System Performance Report provides data and insights from Canadian patients with cancer and their caregivers on experiences with palliative care. Data suggest patients with cancer who die in acute-care hospitals do not always receive inpatient palliative care early in their illness. Over 66% received inpatient palliative care only during their last hospitalization before death, which can be too late for patients to experience the full benefits of this type of physical and emotional support.

Bow Tie Model[3] – The concept of beginning palliative care early in the patient’s journey is illustrated by the “Bow Tie” Model above. The blue triangle represents disease management, including chemotherapy, radiation, surgery and related psychosocial care. The purple triangle represents palliative care, including pain and symptom management and related psychosocial care. The patient’s illness takes them to the possible outcomes of rehabilitation and survival or end-of-life care and death, moving through a complementary continuum of disease management and palliative care, with an increasing emphasis on palliative care toward the end of life.

Included in the report is recent research suggesting that starting palliative care earlier in routine care and treatment planning, and providing this care in the community if the patient desires, can:[4,5]

- reduce unplanned emergency department visits – leaving needed resources to treat emergency patients

- reduce the number of avoidable hospital admissions and shorten hospital stays – which will reduce use of health system resources

- reduce avoidable physical and emotional distress for patients and their families

- increase the opportunity, for patients with terminal cancer, of dying fully supported at home, when desired – a recent survey shows that around 75% of Canadians would prefer to die at home[6]

“There is a misperception that palliative care means end-of-life care. Health-care providers fear that offering this type of care early could reduce hope for a positive outcome, and that discussing ‘palliation’ during cancer treatment could cause anxiety and distress to patients and their families,” said Dr. Camilla Zimmermann, Head of the Palliative Care Division at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. “We must work to end this stigma so that all health-care workers, as well as patients and their families, see palliative care as part of a full cancer care program.”

Palliative and End-of-Life Care reinforces the benefits of having community-based services available so patients are not needlessly hospitalized at the end of their lives. To address this, the Partnership has funded the Paramedics Providing Palliative Care at Home Program in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. This initiative has seen success in training paramedics to provide palliative services to people at home regardless of time of day or location. This has shown to reduce unnecessary hospital visits in these provinces. The Partnership is working to scale up this program and bring it to other provinces and territories.

The report also looks at the need for more research and better data to develop meaningful ways to measure the quality and timeliness of palliative care in Canada. The Partnership recently implemented the Patient Reported Outcomes Initiative in eight provinces. This program has established measurement and reporting cycles at cancer centres and hospitals in these provinces to assess symptoms at all stages of cancer. By routinely tracking symptoms in patients, it will improve understanding of the appropriate timing and delivery of palliative care. The goal in the coming years is to scale up these existing programs and spread to other provinces and territories.

“As a cancer survivor and caregiver for someone with the disease, I have witnessed the benefits of palliative care and how it helps people physically, emotionally and spiritually,” said Penelope Hedges, family caregiver. “I would like to see our health system start to incorporate it earlier in the cancer journey and take steps to remove the stigma around the word ‘palliative care.’ It is not about making people comfortable before they die. It should be considered a normal aspect of cancer treatment.”

“Receiving palliative care at home is dependent upon the active involvement of caregivers,” said Nadine Henningsen, CEO of the Canadian Home Care Association and President of Carers Canada. “Effective home palliative care programs help caregivers understand how they can help their loved ones, what resources are available, who to call when in a crisis and what to expect if their loved one dies at home.”

“We are all affected by cancer in some way. This is why our government supports patients and families with better research, education, treatment and support, including palliative care. We want to ensure that more Canadians can have access to the most appropriate care options that are right for them, when they need them. I thank the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer for adding to the body of knowledge on this important subject and for advocating on behalf of Canadians with cancer so that they can get the best possible palliative care.” — The Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor Minister of Health

A full copy of the report is available at systemperformance.ca.

Data on palliative and end-of-life care in Canada was gathered from: the Canadian Cancer Society, the Canadian Institute for Health Information (which obtained data from the Discharge Abstract Database and National Ambulatory Care Reporting System), and provincial cancer agencies and programs.

–30–

For more information or to arrange interviews, please contact:

Nick Williams

Communications Officer, Media Relations

Canadian Partnership Against Cancer

(416) 915-9222, x5799 (office); (647) 388-9647 (mobile)

About the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer

As the steward of the Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control, the Partnership works with partners to reduce the burden of cancer on Canadians. Our partner network – cancer agencies, health system leaders and experts, and people affected by cancer – brings a wide variety of expertise to every aspect of our work. After 10 years of collaboration, we are accelerating work that improves the effectiveness and efficiency of the cancer control system, aligning shared priorities and mobilizing positive change across the cancer continuum. From 2017-2022, our work is organized under five themes in our strategic plan: quality, equity, seamless patient experience, maximize data impact, sustainable system. The Partnership continues to support the work of the collective cancer community in achieving our shared 30-year goals: a future in which fewer people get cancer, fewer die from cancer and those living with the disease have a better quality of life. The Partnership was created by the federal government in 2006 to move the Strategy into action and receives ongoing funding from Health Canada to continue leading the Strategy with partners from across Canada. Visit www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca.

Notes

1 Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 19;363(8):733-42.

2 Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014 May 17;383(9930):1721-30.

3 The bow tie model of 21st century palliative care. Canadian Virtual Hospice; 2015. Available from: http://www.virtualhospice.ca/

4 Bainbridge D, Seow H, Sussman J, Pond G, Barbera L. Factors associated with not receiving homecare, end-of-life homecare, or early homecare referral among cancer decedents: a population-based cohort study. Health Policy. 2015 Jun;119(6):831-9.

5 Barbera L, Taylor C, Dudgeon D. Why do patients with cancer visit the emergency department near the end of life? CMAJ. 2010 Apr 6;182(6):563-8.

6 What Canadians Say: The Way Forward Survey Report. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association; 2013.