Alcohol policies

Policy actions to reduce alcohol consumption

Recommended policy actions

● Tax alcohol at a high rate and index minimum pricing annually, based on alcohol content and strength.

● Limit outlet density and hours of operation.

● Permit recorking and place limits on number of drinks served.

● Restrict location, quantity, sponsorships, and medium of advertisements.

● Enhance advertising codes to include digital and social media.

● Monitor compliance, introduce prescreening, and enforce advertising regulations.

● Raise the drinking age to 21.

● Eliminate online ordering, delivery services, and brew-on-premise outlets.

● Return to public alcohol retail systems.

● Adopt an evidence-based national alcohol strategy.

● Establish standardized provincial/ territorial alcohol tracking and reporting systems.

● Mandate health and safety messages including links to cancer, standard drink sizes, and information about Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health.

Implemented policy actions

Numerous Canadian municipalities have implemented alcohol policies to reduce harm. See the Policy actions report for further details.

Several provinces and territories have implemented alcohol policies to reduce harm. See the Policy actions report for further details.

The Canadian Alcohol Policy Evaluation (CAPE) identifies 11 policy domains, eight of which have been determined by the Partnership to directly influence consumption and therefore play a strong role in cancer prevention.

For example, alcohol taxation is particularly effective.

Policy domains

Direct effect on consumption and cancer risk:

- Pricing and taxation

- Physical availability

- Marketing and advertising

- Minimum legal drinking age

- Alcohol control system

- National alcohol strategy

- Monitoring and reporting

- Health and safety messaging

Indirect effect on consumption and cancer risk:

- Impaired driving countermeasures

- Liquor law enforcement

- Brief intervention

Pricing and taxation

![]()

Alcohol price and taxes are the most important policy levers to combat consumption and harms, including cancer.1 Higher alcohol prices are strongly associated with lower alcohol consumption.2 Also, consumption can be reduced by increasing the price of strong alcohol and lowering the price for light alcohol.3

Canada is one of a few countries to adopt minimum alcohol pricing. Compare alcohol tax rates among different provinces and territories.

Physical availability

![]()

Alcohol consumption is directly related to availability.4 Density and type of alcohol outlets impact perceptions of drinking and drinking habits.

Restricting hours of sale, days of sale, and movement across borders reduce consumption and alcohol-related cancer.

High outlet density in Toronto5

Toronto has 90 LCBO stores, 66 beer stores, 45 wine retail stores/kiosks and 44 grocery stores to purchase alcohol, along with duty free stores, breweries and wineries, farmers markets, and delivery services.

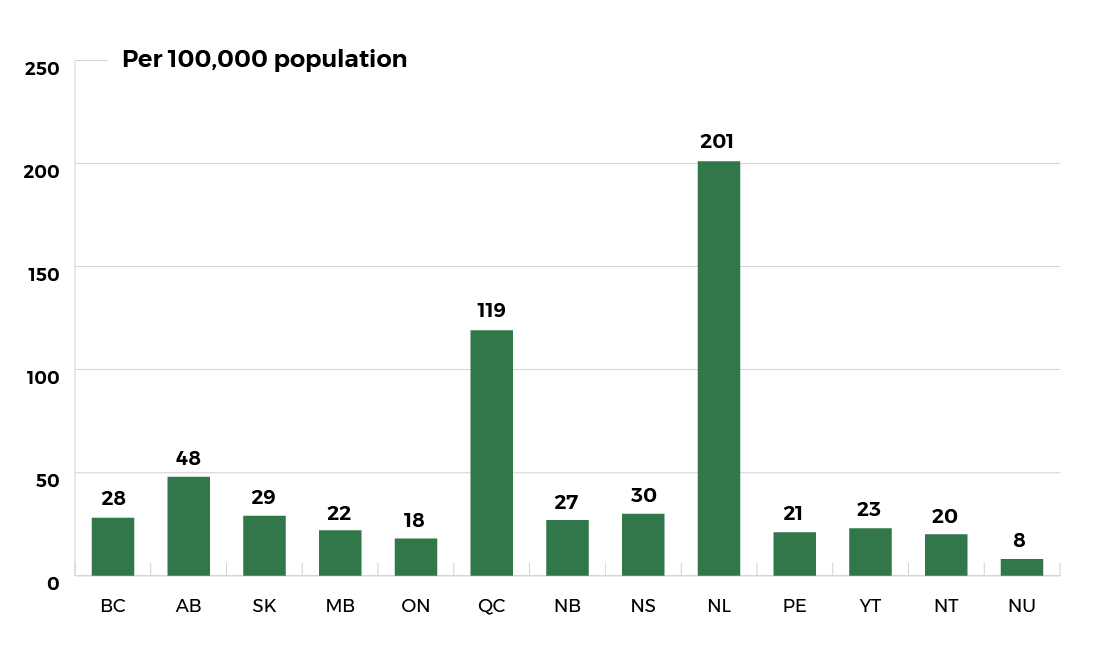

Alcohol retail density in number of stores per 100,000 population (excluding off-sales), by province/territory – 2016

Marketing and advertising

![]()

Alcohol marketing impacts drinking perceptions, early initiation of use, and higher consumption.6 Marketing targeted to young women promotes drinking and exacerbates cancer risks.7 In Canada, restrictions on youth marketing have failed as few provinces and territories have any restrictions on alcohol advertising and promotions. But many local governments have used bylaws to restrict alcohol advertising and promotions.

Alcohol advertisement controls in Brampton8

The Municipal Alcohol Policy of Brampton, Ontario prohibits alcohol advertising at venues attended by those under 19 and alcohol cannot be advertised as the main activity of any event.

Minimum legal drinking age

With a few exceptions, the minimum legal drinking age in Canada is 19 years old. Higher drinking ages result in delayed first use and less heavy drinking among youth.9 The lower the drinking age the higher number of deaths among young men.10

Alcohol control systems

![]() Most provinces have a mixed alcohol retail system where government sells alcohol alongside privately-owned outlets. Public alcohol systems reduce harms through minimum pricing, availability controls, and limits on marketing.11 Only PEI and the territories operate under a public alcohol retail system.

Most provinces have a mixed alcohol retail system where government sells alcohol alongside privately-owned outlets. Public alcohol systems reduce harms through minimum pricing, availability controls, and limits on marketing.11 Only PEI and the territories operate under a public alcohol retail system.

Alcohol strategies

![]() A federal alcohol strategy is essential to reduce alcohol-related harms, including cancer.12 A revised National Alcohol Strategy is scheduled to be released in 2022.

A federal alcohol strategy is essential to reduce alcohol-related harms, including cancer.12 A revised National Alcohol Strategy is scheduled to be released in 2022.

Several provinces/territories have their own alcohol strategies, but few consider the risk of cancer. Municipal alcohol policies are part of a multi-faceted approach to reducing alcohol-related harms.

Community Alcohol Strategy in Wolfville13

Working in partnership with Acadia University, RCMP, businesses, and health authorities, Wolfville, Nova Scotia’s Community Alcohol Strategy aims to create partnership cohesion and educate the public about high-risk drinking and harm reduction, as well as balance negative impacts of over-consumption with promotion of local craft beverages.

Monitoring and reporting

![]() Monitoring and reporting of trends inform policies that reduce alcohol-related cancers. Most provinces/territories have reporting systems to track alcohol indicators. Various health organizations collect and report on alcohol metrics including hospitalizations, per capita consumption, cancer rates, and crime.

Monitoring and reporting of trends inform policies that reduce alcohol-related cancers. Most provinces/territories have reporting systems to track alcohol indicators. Various health organizations collect and report on alcohol metrics including hospitalizations, per capita consumption, cancer rates, and crime.

Alcohol reporting sources

- Health Canada: Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey

- Health Canada: Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring

- CIHI: Hospitalizations Entirely Caused by Alcohol

- CIHI: Alcohol Harm in Canada

- CCSA: Canada Substance Use Costs and Harms (CSUCH)

- Statistics Canada: Control and sale of alcoholic beverages, year ending March 31, 2019

- Beer Canada: National Overview

Health and safety messaging

![]() Health and safety messaging can increase knowledge about consumption trends, acute harms, and legislation around alcohol. Warning labels reduce alcohol sales and create awareness around drinking guidance, standard drink sizes, cancer risks, and other harms.14

Health and safety messaging can increase knowledge about consumption trends, acute harms, and legislation around alcohol. Warning labels reduce alcohol sales and create awareness around drinking guidance, standard drink sizes, cancer risks, and other harms.14

Health messaging in Toronto15

Events held in Toronto must have information posted on RIDE programs, drinking during pregnancy, minimum legal drinking age, and guidance around consumption. Industry-sponsored events must contain messaging about responsible consumption and alcohol cannot be advertised as the main activity of any event.

Impacts of the COVID-9 pandemic

COVID-19 and alcohol sales

- Nearly 1 in 5 Canadians 18+ increased alcohol consumption during the pandemic due to schedule disruptions, stress, and boredom.16

- Except PEI, every province and territory deemed alcohol as essential during the pandemic.17

- The pandemic saw a loosening of alcohol policies including expanded hours of sale, delivery of alcohol, curbside pick-up, and drinking permitted in public parks.

- Implementing stricter alcohol policies following the pandemic will reduce consumption and harms.18

Visit the Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction for current data and updates.

Pandemic pick-up and delivery

During the pandemic, alcohol delivery and pick-up was expanded across several provinces and territories. Ontario and BC now allow alcohol to be delivered with the purchase of food, while Alberta allows for the delivery of alcohol alone.

Some have implemented permanent measures beyond the pandemic, including Newfoundland and Labrador, which has amended regulations to allow for alcohol delivery services indefinitely.

- Stockwell T, Leng J, Sturge J. Alcohol Pricing and Public Health in Canada: Issues and Opportunities. Victoria, BC: Centre for Addictions Research of BC, University of Victoria; 2006. Cited 30 January 2021. Available from: https:// www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/ report-alcohol-pricing-public-health-cnd.pdf.

- Giesbrecht N, Wettlaufer A, Thomas G, Stockwell T, Thompson K, April N et al. Pricing of alcohol in Canada: A comparison of provincial policies and harm-reduction opportunities. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2015;35(3):289-297.

- Ibid.

- Sherk A, Stockwell T, Chikritzhs T, Andréasson S, Angus C, Gripenberg J et al. Alcohol Consumption and the Physical Availability of Take-Away Alcohol: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of the Days and Hours of Sale and Outlet Density. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018. Cited 30 January 2021;79(1):58-67. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29227232/

- Medical Officer of Health. Public Health Implications of the Proposed Increase in Access to Alcohol in Ontario. 2019. Cited 26 February 2021. Available from: https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2019/hl/bgrd/backgroundfile-135645.pdf.

- Monteiro M, Babor T, Jernigan D, Brookes C. Alcohol marketing regulation: from research to public policy. Addiction. 2017;112:3-6.

- Mart S, Giesbrecht N. Red flags on pinkwashed drinks: contradictions and dangers in marketing alcohol to prevent cancer. Addiction. 2015;110(10):1541-1548.

- City of Brampton. Municipal Alcohol Policy. 2016. Available from: https://www.brampton.ca/EN/residents/Recreation/BookingsRentals/Documents/Municipal%20Alcohol%20 Policy/Municipal%20Alcohol%20Policy.pdf.

- Alcohol Policy Framework. Toronto, ON: CAMH; 2019. Cited 30 January 2021. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdfs—publicpolicy-submissions/camh-alcoholpolicyframework2019-pdf.f?la=en&hash=6DCD59D94B92B BC148A8D6F6F4A8EAA6D2F6E09B.

- Callaghan R, Sanches M, Gatley J, Stockwell T. Impacts of drinking-age laws on mortality in Canada, 1980–2009. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;138:137-145.

- Stockwell T, Wettlaufer A, Vallance K, Chow C, Giesbrecht N, April N et al. Strategies to Reduce Alcohol-Related Harms and Costs in Canada: A Review of Provincial and Territorial Policies. Victoria, BC: Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research; 2019. Cited 30 January 2021. Available from: https://www.uvic.ca/research/ centres/cisur/assets/docs/report-cape-pt-en.pdf

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use. Recommendations for a National Alcohol Strategy. 2007. Cited 1 February 2021. Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/ default/files/2019-05/ccsa-023876-2007.pdf

- Wolfville Operations Plan 2020-2024. 2020. Cited 26 February 2021. Available from: https://wolfville.ca/component/ com_docman/Itemid,264/alias,2730- operational-plan-and-budget-2020-21-final-2/ category_slug,140-finance/view,download/

- Effectiveness of Approaches to Communicate Alcohol related Health Messaging: Review and implications for Ontario’s public health practitioners. Toronto, ON: Queens Printer for Ontario; 2013. Cited 31 January 2021. Available from: https://www. publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/A/2015/alcohol-health-messaging.pdf?la=en.

- Medical Officer of Health. Public Health Implications of the Proposed Increase in Access to Alcohol in Ontario. 2019. Available from: https://www.toronto.ca/ legdocs/mmis/2019/hl/bgrd/backgroundfile-135645.pdf.

- COVID-19 and Increased Alcohol Consumption: NANOS Poll Summary Report. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction; 2020. Cited 30 January 2021. Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/ sites/default/files/2020-04/CCSA-NANOS-AlcoholConsumption-During-COVID-19-Report-2020-en.pdf

- Stockwell T, Andreasson S, Cherpitel C, Chikritzhs T, Dangardt F, Holder H et al. The burden of alcohol on health care during COVID‐19. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2020;40(1):3-7

- Ibid.