Eliminating cervical cancer in Canada

Improving HPV vaccination rates

Key takeaways

- The HPV vaccine is safe and effective in preventing cervical cancer and data continues to demonstrate its safety and effectiveness.1,2,3,4,5,6,7

- Publicly funded, school-based and catch-up HPV vaccination programs are available in all provinces and territories.2

Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by long-lasting infection with certain types of the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV infection can also cause cancers of the vulva, vagina, penis and anus, as well as certain head and neck cancers.8 However, safe and effective HPV vaccines have been available and used in Canada for over 15 years2—and can prevent the kinds of infections that lead to cancer.3,4

In 2007, some provinces introduced the publicly funded HPV vaccination programs for girls and, by 2017, all provinces and territories had publicly funded HPV vaccination programs for girls and boys.2 These programs provide an effective and equitable means to reach young people and are foundational to preventing cervical cancer, but coverage, eligibility and access vary significantly across the country. For instance, many people who would benefit from HPV vaccination do not qualify for publicly funded programs and face a financial barrier of spending hundreds of dollars out-of-pocket. At minimum, the publicly funded HPV vaccine should be available to anyone who was previously eligible for it but did not receive it (once eligible, always eligible). Explore the specific actions needed for Canada to continue to improve and expand HPV vaccination.

As of 2023, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador are the only provinces/territories with a “once eligible, always eligible” policy, allowing all people who were previously offered the HPV vaccine but did not receive it to get it for free.

[We should be] extending the vaccination eligibility and coverage [to] get a wider population vaccinated—hopefully free of charge if that’s possible. It is a very expensive vaccination when you’re outside of the school-based program.

Natasha Lam, Patient & Family Advisor, Canadian Partnership Against Cancer

Centering equity and reconciliation

Equity-denied individuals—including those who identify as 2SLGBTQIA+, those who identify as visible minorities, those who live in rural and remote locations, and those who are from lower-income neighbourhoods—may experience specific, distinct and intersectional barriers to accessing HPV vaccines.9,10 Identifying and addressing these inequities and barriers is a central focus of the Action Plan, which also calls for the implementation of Peoples-specific actions related to HPV vaccination and cervical cancer prevention and care for First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

These actions must be embedded into any work on improving HPV vaccination rates across Canada and done in collaboration with First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners. The Urban Public Health Network (UPHN) is centering equity and reconciliation in its collaborative work with partners across Canada to increase HPV vaccine uptake among equity-denied populations, including First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities.

Hear from Dr. Angeline Letendre, Vice President and Research Chair, Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association, about the importance of this priority.

Story of progress

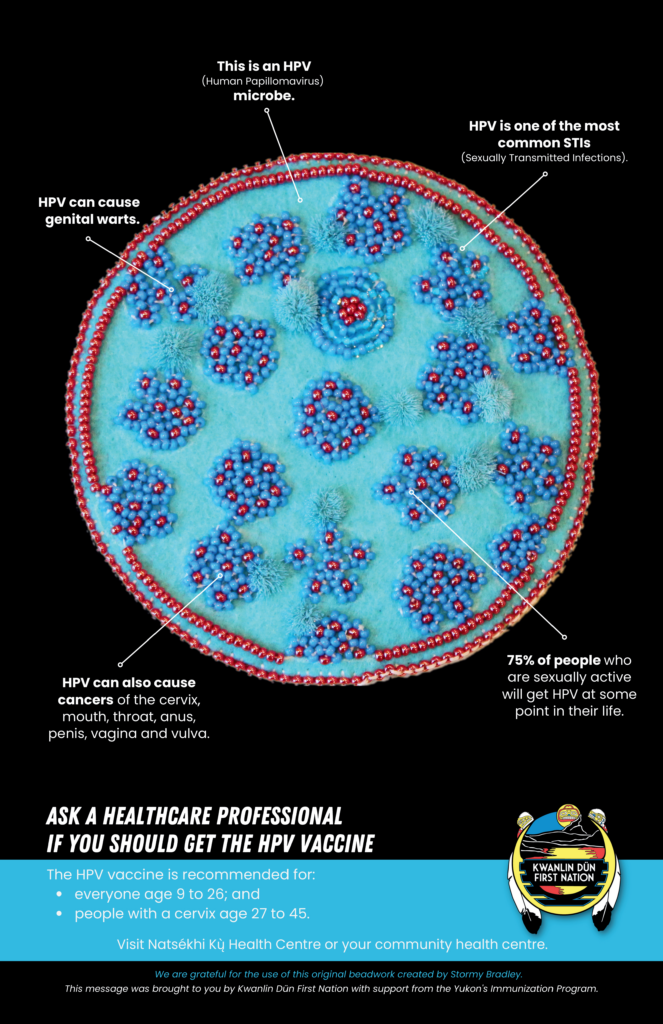

An arts-based approach to raising awareness about the HPV vaccine

Drawing on evidence about the role of art in health promotion, Kwanlin Dün First Nation partnered with Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in artist Stormy Bradley to raise awareness about the HPV vaccine.11 Stormy’s artwork is centered on the strength of Indigenous women, reclaiming and destigmatizing Indigenous sexuality and critiquing misogyny in mass media. Using beadwork, Stormy depicted an HPV microbe, a healthy cervix and a cervix with HPV. Photos of her work were used for posters as part of a campaign to raise awareness about the HPV vaccine. The campaign resulted in meaningful community discussions, active interest from community members, and a significant increase in awareness and vaccine coverage in the local population.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV vaccination is safe and effective [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021 [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccinesafety.html

- Goyette A, Yen GP, Racovitan V, Bhangu P, Kothari S, Franco EL. Evolution of public health human papillomavirus immunization programs in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2021 Feb 22;28(1):991-1007. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28010097.

- de Sanjosé S, Serrano B, Tous S, Alejo M, Lloveras B, Quirós B, et al. Burden of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers attributable to HPVs 6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52 and 58. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019 Jan 7;2(4):pky045. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky045.

- Government of Canada. Human papillomavirus vaccine: Canadian immunization guide. Part 4: active vaccines [Internet]. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2018 [cited 2024 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-9-human-papillomavirus-vaccine.html#a5.

- Donken R, van Niekerk D, Hamm J, Spinelli JJ, Smith L, Sadarangani M, et al. Declining rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in British Columbia, Canada: an ecological analysis on the effects of the school-based human papillomavirus vaccination program. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jul 1;149(1):191-199. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33513.

- Racey CS, Albert A, Donken R, Smith L, Spinelli JJ, Pedersen H, et al. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia rates in British Columbia women: a population-level data linkage evaluation of the school-based HPV immunization program. J Infec Dis. 2020 Jan;221(1):81-90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz422.

- Palmer TJ, Kavanagh K, Cuschieri K, Cameron R, Graham C, Wilson A, et al. Invasive cervical cancer incidence following bivalent human papillomavirus vaccination: a population-based observational study of age at immunization, dose, and deprivation. JNCI. 2024 Jan 22. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djad263.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, vol. 90: Human papillomaviruses. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007.

- Amiling R, Winer RL, Newcomb ME, Gorbach PM, Lin J, Crosby RA, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among young, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and transgender women – 3 U.S. cities, 2016-2018. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021 Dec 2;17(12):5407-5412. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.2005436.

- Henderson RI, Shea-Budgell M, Healy C, Letendre A, Bill L, Healy B, et al. First Nations people’s perspectives on barriers and supports for enhancing HPV vaccination: foundations for sustainable, community-driven strategies. Gynecologic Oncology. 2018;149:93-100.

- Flicker S, Danforth JY, Wilson C, Oliver V, Larkin J, Restoule J, et al. “Because we have really unique art”: decolonizing research with Indigenous youth using the arts. International Journal of Indigenous Health. 2014;10(1),16-34. doi: 10.18357/ijih.101201513271.