Beginning the journey into the spirit world

First Nations, Inuit and Métis approaches to palliative and end-of-life care in Canada

In response to recommendations from First Nations, Inuit and Métis Elders, Knowledge Carriers, community health professionals and researchers, all with experience and knowledge of Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care, the Partnership funded development of Beginning the journey into the spirit world: First Nations, Inuit and Métis approaches to palliative and end-of-life care in Canada.

This resource summarizes factors contributing to First Nations, Inuit and Métis palliative and end-of-life care experiences; identifies areas for action in palliative and end-of-life care based on priorities, gaps, challenges and needs expressed by First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and communities; and identifies innovative and Indigenous community-based models of care and person-centred approaches to palliative and end-of-life care.

Resources at a glance

Indigenous perspectives and considerations on palliative and end-of-life care

For many First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, their families and communities, dying and death are not just about biomedical and physical processes. It is about an individual’s transition to the spirit world—a social and spiritual event to be honoured and celebrated as a collective.

For many First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, their families and communities, dying and death are not just about biomedical and physical processes. It is about an individual’s transition to the spirit world—a social and spiritual event to be honoured and celebrated as a collective.

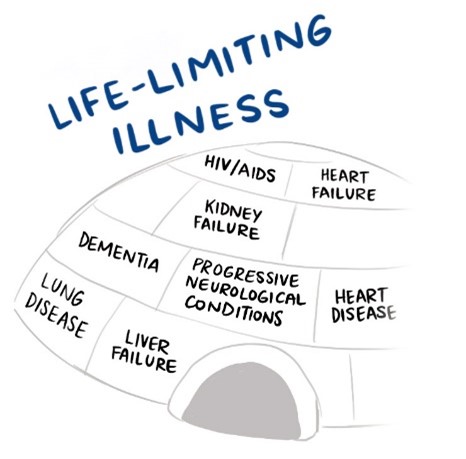

Many factors influence palliative and end-of-life care for Indigenous Peoples.1,2,3 Some of these factors are:

- historical factors, for example, history of colonization, intergenerational trauma, health inequities and stigma associated with life-limiting illnesses, dying and death

- jurisdictional factors, for example, access to palliative and end-of-life care based on health-care jurisdiction and funding

- cross-cultural factors, for example, cultural resiliency and resurgence; connection or reconnection to land, people, family, place, languages and Indigenous spirituality

- capacity building factors, for example, development of knowledge, skills and abilities to participate in any or all aspects of decision-making in communities, regions, provinces/territories and the country as a whole; includes program planning and development to implementation and evaluation intended to enhance holistic palliative and end-of-life care

- resource factors, for example, access to the basic needs in life, high-quality health services, resources and supports

We cannot fully recognize the health inequities for Indigenous Peoples in Canada without understanding how historical, social, cultural and political factors over time have and continue to shape relationships between institutions such as the health-care system and Indigenous Peoples and their communities. Health inequities, the historical effects of colonization and the residential school system in Canada are interrelated. When groups of individuals are oppressed and marginalized by state policies, laws and organizational systems by devaluing their ways of being and knowing, intergenerational trauma results which disrupts First Nations, Inuit and Métis cultures, languages, values, practices and histories.

To support cultural safety, it is important for allies (individuals, groups and organizations working with and alongside First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples) to have access to timely, relevant and culturally congruent palliative and end-of-life care strategies, promising practices and resources. It is also beneficial for allies to enhance their competencies (knowledge, skills and abilities), understanding of and interpersonal communications with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples living with life-limiting illnesses, their families and communities.

Culture as medicine

Culture is a complex concept that refers to many aspects of living and being in the world.

Many First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities understand that a way to enhance individual, family and community healing and helping is through culturally congruent practices. When culture is a core component to healing and helping, there are opportunities for programs, policies and broader strategies to honour relationships to land, people and place; Indigenous spirituality and connections with our ancestors; and the role of families, friends and communities.

Culture as medicine recognizes the value of relationships in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities’ cultures and traditions. Indigenous approaches to healing and helping are often linked to land and place through songs, stories, ceremonies, language and writing. As such, land and place are often important dimensions of cultural identity, healing and helping (physical, mental, emotional and spiritual dimensions) for many Indigenous Peoples across Canada.

Culture as medicine recognizes the value of relationships in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities’ cultures and traditions. Indigenous approaches to healing and helping are often linked to land and place through songs, stories, ceremonies, language and writing. As such, land and place are often important dimensions of cultural identity, healing and helping (physical, mental, emotional and spiritual dimensions) for many Indigenous Peoples across Canada.

Also, strengths and ways of knowing are present in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities in the form of Elders and Knowledge Carriers, Indigenous healers and helpers, community leaders, families and friends who support relational healing and helping.

Relational healing and helping practices in palliative and end-of-life care facilitate healthy ways to experience grief, loss and bereavement. These practices help people and groups to develop a greater sense of connectedness to self, families, friends, community members, communities (as a whole) and Mother Earth, each of which influences how individuals and groups can understand illness, dying, death and loss.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis cultures support resiliency in terms of the ability of people, their families and communities to flourish and adapt to situations and/or environments with minimal negative effects during hardships or crises and/or after a change. From a healing and helping perspective, resilience emphasizes a person’s and/or group’s ability to effectively draw on strengths and capabilities rather than focus on weaknesses or pathologies.

Braiding Indigenous ways of knowing and biomedical approaches in palliative and end-of-life care

Braiding (or harmonizing) Indigenous and non-Indigenous ways of knowing can be used in a way that is mutually respectful and reciprocal. In this context, braiding palliative and end-of-life care can include:

- Etuaptmumk/two-eyed seeing

- trauma-informed care

- care across the generations

- resilience-informed care

- gender- and 2SLGBTQQIA+ -informed care

- relationships and allyship

Promising practices

There is a need for all healthcare providers in various organizational settings across Canada to have both palliative care and cultural safety foundational training as part of their healthcare practices and continuous learning. Many organizations have implemented programs to achieve these goals.

Readers are invited to use a distinctions-based approach in their interpretation of this report and any actions taken in developing and implementing strategies, programs and resources in palliative and end-of-life care.

This report is not a “how-to” clinical manual, nor is it intended to be prescriptive as a “one size fits all” for First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities across Canada.

It is important to recognize that there is a vast number of First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities across Canada in urban, rural, remote and northern areas.

Each community may have unique ways to support individuals with life-limiting illnesses in their transition to the spirit world.

Therefore, representation and adaptability of all of the promising practices presented in this report may vary based on the protocols, customs, languages and practices relative to community connections and family lineages.

1. Caxaj CS, Schill K, Janke R. Priorities and challenges for a palliative approach to care for rural Indigenous populations: a scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2018;26(3):e329—e336.

2. http://www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/55/4/394.full.pdf

3. Lemchuk-Favel L. The provision of palliative end-of-life care services in First Nations and Inuit communities. FAV COM; 2016, January.