Beginning the journey into the spirit world

In this section:

- Land and place-based healing and helping

- Indigenous languages

- Indigenous spirituality and connections with ancestors

- Role of ancestors

- Role of healing ceremonies, teachings, practices and medicine

- Role of Elders and Knowledge Carriers

- Role of Indigenous healers and helpers

- Role of community leaders

- Role of families and friends

Land and place-based healing and helping

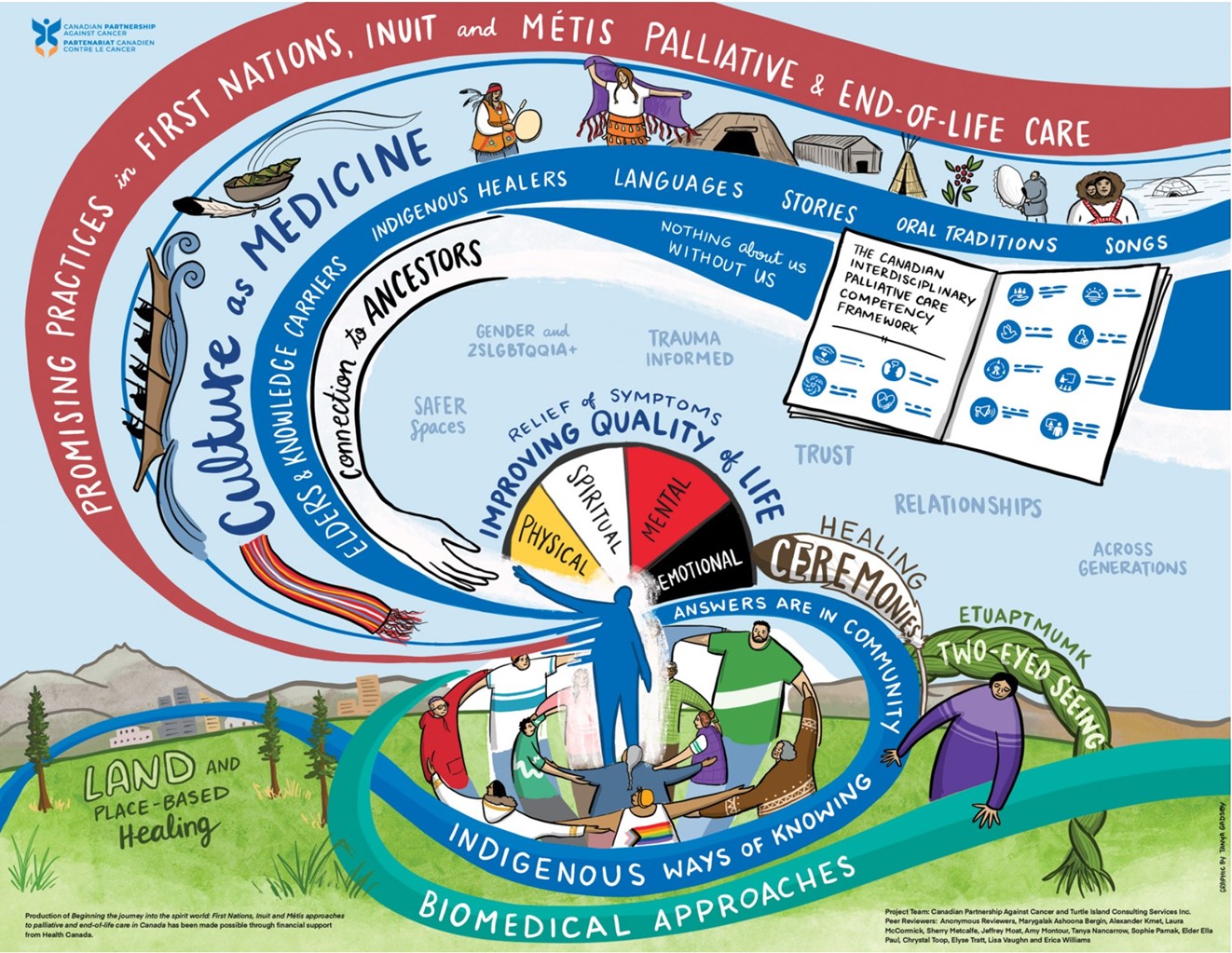

Land and community can be viewed as healers and helpers for many First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples in Canada. Since time immemorial, Indigenous Peoples developed their cultures, languages and ways of knowing through their understanding of and relationships with land, people and place (community). Therefore, in addition to using biomedical-based palliative and end-of-life care supports and resources, it is equally important to acknowledge and recognize how cultural ceremonies, rituals and related spiritual practices are medicine for many Indigenous Peoples.

In managing a transition from a colonial to a de-colonial world, from the land to the community, and from adversity to whole health, land-based practices, and knowledges central to Indigenous resilience aim to integrate cultural processes into the everyday, while ensuring seamless continuity for those in need.1

Land and place-based healing and helping include a variety of activities such as:

- drumming, singing, dancing and praying

- performing rites of passage (for example, funerals)

- connecting to nature: cleansing, reconnecting to something larger than ourselves

- listening to Elders’ and Knowledge Carriers’ stories and guidance

- involving community, for example, sharing food/meals with family and community, playing music with family and community

Land and place-based healing and helping programs are community-driven and are developed in response to specific health priorities (for example, palliative and end-of-life care) for communities. Knowledge Carriers and Elders are engaged in land and place-based healing and helping from planning to implementation, and these programs are based on localized culturally specific worldviews, including values and healing practices.

Language is another dimension to delivering land and place-based healing and helping especially knowledge such as place names, cultural practices and local area history.2

Indigenous languages

There are a vast array of Indigenous languages across Canada with over 70 Indigenous languages being spoken. For an interactive map of Indigenous languages in Canada, visit NativeLand.ca.

In the spirit of cultural revitalization, access, use and interpretation of Indigenous languages during palliative and end-of-life care can improve communications and information management by:

- improving health-care system navigation for families and caregivers using an Indigenous health navigation program3,4

- improving locally and culturally effective healing and helping messages through a better understanding of Indigenous health beliefs5

- making available and using Indigenous interpretation services6

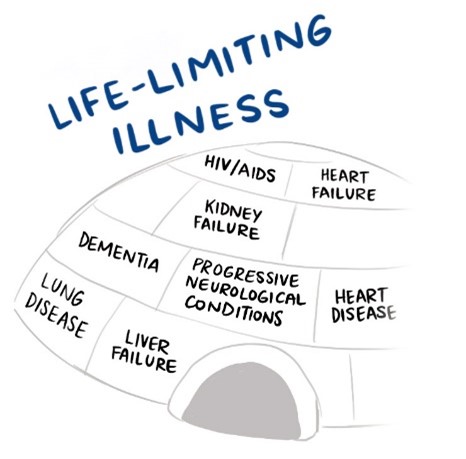

The use of Indigenous languages describing palliative and end-of-life care7 can help reduce hesitancy for people with life-limiting illnesses. Use of Indigenous languages can also minimize the use of biomedical jargon and formality while centering the continuum of care on Indigenous Peoples’ individual and collective experiences and ensuring accessibility to Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care.8,9

Indigenous spirituality and connections with ancestors

For many First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, their families and communities, dying and death are not just about biomedical and physical processes. It is about an individual’s journey to the spirit world—a social and spiritual event to be honoured and celebrated as a collective.

While religion usually entails adhering to a certain belief system, spirituality is the quality of being concerned with the human spirit or soul as opposed to material or physical things. The soul is the spiritual part of a human being regarded as immortal.

Gaining competencies and comfort in braiding spirituality with palliative and end-of-life care aids in:

- honouring the holistic self—mind, body and spirit

- raising awareness of spirituality of people with life-limiting illnesses

- recognizing spiritual values as a source of strength during illness, dying and death that help many make sense and meaning out of the purpose of our lives on earth

- helping people living with life-limiting illnesses connect with their own powers of thinking, feeling, deciding, willing and acting

Role of ancestors

![]()

Voices from the community

“I’m scared because I’ve never died before,” he stated. And I said, “well, I’m scared too, I’ve never seen somebody die.”

I was 18 years old and my husband was 23 years old when he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Despite having cancer, he lived six years in fairly good health. When my husband was 29 years old, tumours popped out everywhere. He told me, “Ella, please don’t let them put me in the hospital.”

He felt that the hospital was going to do everything in their power to keep him alive regardless and he simply said, “I do not want to live any longer than I need to be.”

Based on his request, my family and I kept him home during his care. He was prescribed pharmaceutical medicine because he was in a lot of pain.

My husband dealt with the pain but he was afraid. He kept seeing people and inviting them in for tea and coffee. I did not see these people as they were some of our ancestors. I believe they came to help my husband begin his journey to the spirit world.

On his last day alive, he asked me if I was ready (for him to die). I said “no, I wasn’t” but I guess I would have to be. Then, he asked if I was going to be there when he died. I said, “yes, I would be there.”

I’m scared because I’ve never died before,” he stated. And I said, “well, I’m scared too, I’ve never seen somebody die.

While my husband was dying, he was surrounded by his family, friends, prayers and traditional medicine. We brought in a traditional Indigenous medicine person who carries out sweats and he brought in traditional medicine. We also had a (non-Indigenous) preacher visit us – he was a good friend of the family.

As my husband was beginning his journey (to the spirit world), it was like somebody just turned down the volume. It was also like I could almost physically see the door that my husband was preparing to go through. I could almost see it. It was like clearer and clearer space. I could almost see him go through that space. But it was like I knew I couldn’t go there.

The next morning, my husband went. It was very peaceful for him but very lonely for me.

My husband planned everything. He planned his whole funeral including what he was going to wear in his casket. I didn’t have to worry about how to comb his hair or what clothes to put on him or anything. He had it all picked out and arranged. My husband had everything laid out. He did this to make sure there was not a lot of stuff on my plate to do after he was gone – as I was raising our son.

So, that was my husband. I still miss him and that was 46 years ago.

In my other palliative care experiences with friends and as a helper for individuals with life-limiting illnesses, I’ve seen “this door and space” a few times since, and it’s just over there. I know that I’m not to go over there yet, so it’s like I know it’s there, though. These experiences have made me more aware of the power of care.

-Ella Paul, Mi’kmaw Elder

Using a spiritual and ancestral lens, palliative and end-of-life care has the opportunity to create safer spaces to braid cultural practices and decision-making during the dying process and after death ceremonies.

For First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples living with life-limiting illnesses, their families and communities, culture and spirituality can protect against experiences of cultural and social isolation.

Indigenous spirituality and connecting with ancestors can establish or re-establish Indigenous identity and belonging, particularly when one is transcending from the physical life to the spirit life.

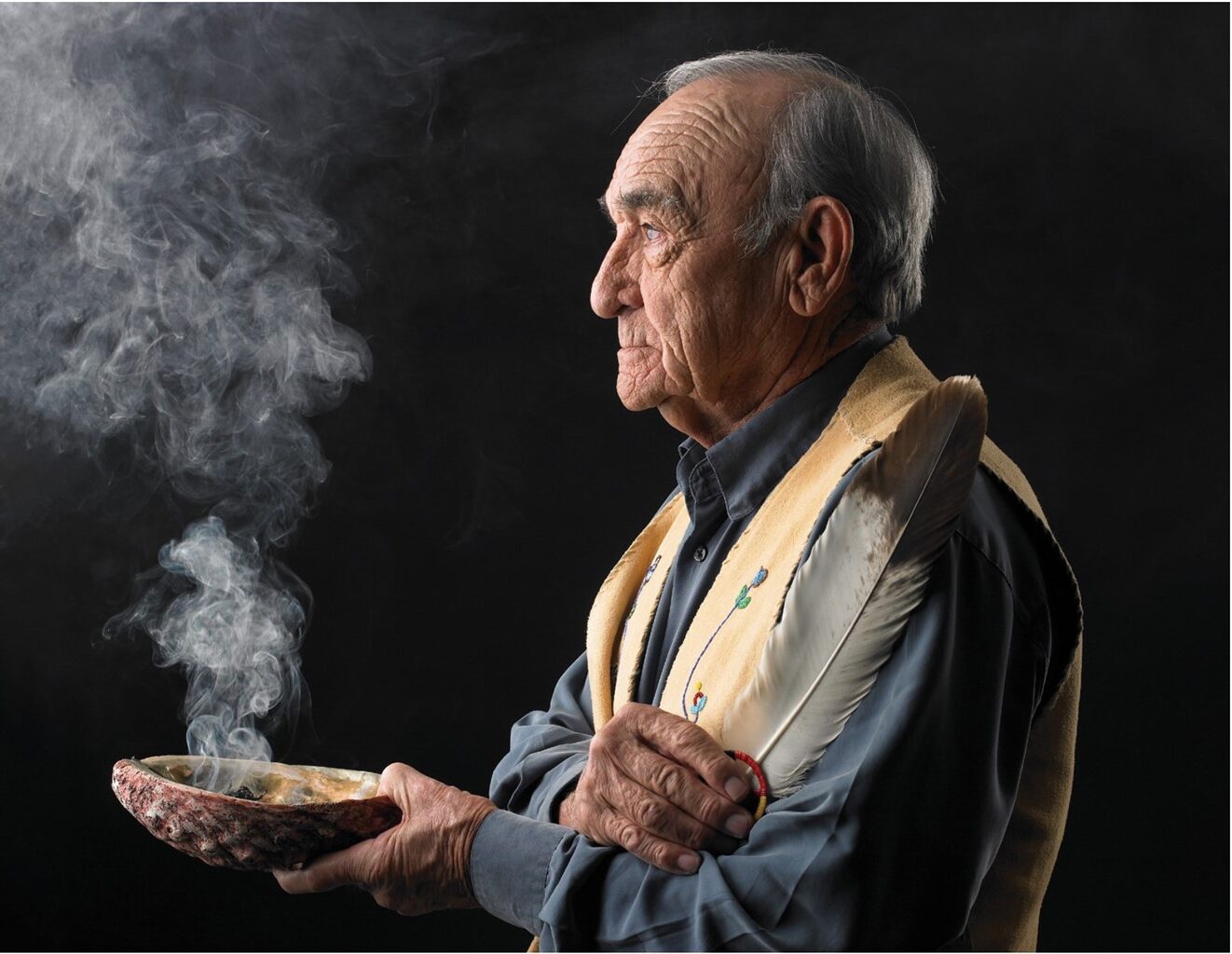

Role of healing ceremonies, teachings, practices and medicine

Healing ceremonies, teachings and medicine are sacred spiritual practices and ways of Indigenous cultural continuity which aid in Indigenous identities, cultural resurgence and resistance to colonization and assimilation.

In palliative and end-of-life care, opportunities exist to expand the continuum of care for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples living with life-limiting illnesses, their families and communities by updating health-care policies, procedures and protocols to allow Indigenous cultural practices and ceremonies (for example, smudging,10 engaging in pipe ceremonies,11 engaging in sweat lodge ceremonies,12 drumming and praying) in health-care institutions (for example, hospitals), including the culturally appropriate preparation of the body after death.13

In palliative and end-of-life care, opportunities exist to expand the continuum of care for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples living with life-limiting illnesses, their families and communities by updating health-care policies, procedures and protocols to allow Indigenous cultural practices and ceremonies (for example, smudging,10 engaging in pipe ceremonies,11 engaging in sweat lodge ceremonies,12 drumming and praying) in health-care institutions (for example, hospitals), including the culturally appropriate preparation of the body after death.13

When discussing healing ceremonies, teachings, practices and medicine, the issue of cultural appropriation often arises in relation to the use, teaching and application of Indigenous spiritual practices and rituals. As an ethical practice, experiential teachings and supervision with recognized Elders, Knowledge Carriers and/or healers is needed to continue one’s safer and respectful use of Indigenous spiritual practices in one’s given helping profession which includes palliative and end-of-life care.

Why is cultural appropriation disrespectful? The answers are in the community.

Many Indigenous communities across Canada do most of the holistic caring for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples. Communities know what to do.

Strengths and ways of knowing are in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities in the form of Elders and Knowledge Carriers, Indigenous healers and helpers, community leaders, families and friends.

Relational healing and helping practices in palliative and end-of-life care facilitate healthy ways to experience grief, loss and bereavement. These practices help people and groups to develop a greater sense of connectedness to self, families, friends, community members, communities (as a whole) and Mother Earth, each of which influences how individuals and groups can understand illness, dying, death and loss.

To hear oral stories about the role of healing ceremonies, teachings and practices from First Nations, Inuit and Métis perspectives, visit Living my Culture.

Voices from the community: Perspectives from Inuit in Nunavik on palliative and end-of-life care

Community Elders and spiritual leaders explained that historically, once death occurred, bodies were placed under an oblong pile of rocks as the frozen tundra prevented bodies from being buried. Included were a person’s key possessions such as hunting, carving, cooking and sewing tools. The rocks covering the body prevented predatory birds and mammals from preying on the deceased. In parts of Nunavik, these graves are now preserved and protected with fencing. In Nunavik communities, extended family and community members continue traditions in which immediate caregivers keep vigil during the last days of a patient’s life. More recently, members of the women’s auxiliary, a church-based volunteer group, assist in cleaning, cooking, keeping vigil, recruiting volunteers, if needed, and in washing bodies after death. These practices remain active.14

Promising practice: Canadian Virtual Hospice at Livingmyculture.ca

Livingmyculture.ca is a repository of First Nations, Inuit and Métis stories and wisdom about living with serious illnesses, end-of-life, grief and loss and supporting others.

This website also contains multi-media resources, including more than 800 video clips in the oral storytelling tradition by people living with serious illnesses, families, Elders, Indigenous health-care providers and community leaders; four online cultural safety learning modules for health-care providers and educators; webinar recordings; online materials and print-based formats.

The primary audiences are Indigenous Peoples, health-care providers working with and alongside Indigenous Peoples and educators building the capacity of health-care providers to provide culturally safer care.

First Nations perspectives on illness, palliative and end-of-life care: First Nations

Inuit perspectives on illness, palliative and end-of-life care: Inuit

Métis perspectives on illness, palliative and end-of-life care: Métis

Role of Elders and Knowledge Carriers

![]()

Voices from the community

My friend’s son called me. He said, “will you come down (to the hospital) and smudge mom?” I said, yes and that I would be right there.

My friend died of cancer two years ago. The cancer attacked different parts of her body and she was in so much pain. We had a lot in common: we were both widows, both had two sons and we were both the same age.

I often went out to lunch with her and took her on drives around the community. She enjoyed the company – she talked a lot and laughed quite a bit. I remember one car ride during the fall. The leaves were red and crimson and my friend, though in pain, commented on the beauty of nature – in particular, the trees.

Unfortunately, she kept getting sicker and weaker. So, she went into the hospital. My friend was dying.

When I went to visit my friend, her hair was messy and she had a dirty old t-shirt on. I was annoyed with the nurses for not cleaning her up because my friend is a very prim and proper lady.

The next day, I bought her a bunch of night gowns and I took them to her to wear. The new night wear helped her mood and changed her outlook. I helped her change into her new clothes. My friend said that wearing the new nightgowns made her feel clean and so much better even though she was in pain.

A few days later, I got a call in the morning. My friend’s son called me. He said, “will you come down (to the hospital) and smudge mom?” I said, yes and that I would be right there.

When my friend’s son called me, I didn’t know if she had died or if she was still alive. When I got to the hospital, my friend was still alive. I took my oldest son with me because death has really bothered him since my husband died over four decades ago. I wanted him to see the natural journey of life – how it’s sad for us, but not necessarily for the person beginning their journey to the spirit world.

My friend’s family were already in her hospital room. I arrived with my son…so we went into the room. They shut the door and I smudged everybody first. Her sons, and then her daughter-in-law, then her sister, her niece and my son. And then, I started to smudge my friend all around her body while I was praying.

It was really hard for me but I just kept focusing on praying. I started the smudge from her feet and all the way up her body. I then touched the feather on my friend’s forehead and then on her chest. My eyes were closed during the smudge and prayers, I didn’t see it but my friend’s daughter and her sister said as soon as I touched her chest, my friend took her last breath. They said, “you helped her, you helped her leave.” I’m really glad I did help her. I miss her and I still miss her crazy sense of humour!

As some of my friends have gone over the years, I miss them. However, they’re all gone to that different space. We have to be here for them and I think that’s kind of what my job is for friends and individuals with life-limiting illnesses, it’s being there for them.

– Ella Paul, Mi’kmaw Elder

Elders15 and Knowledge Carriers16 hold important roles in sharing traditional values and sacred teachings. They individually and collectively bring wisdom and experience to palliative and end-of-life care. Their understanding of specific First Nations, Inuit and Métis traditions and cultural expectations around dying and death enables conversations and facilitates dying and death to happen in a good way.

A good way

According to some Indigenous perspectives and ways of knowing, a good way can refer to the acts of doing your best; being honest, authentic, and sincere; meaning well; speaking well; acting well; following cultural protocols; and carrying out actions for the benefit of others in addition to yourself.

Role of Indigenous healers and helpers

Indigenous healers17 and helpers can bridge culture, land, identity and place as part of the healing medicines that aid people living with life-limiting illnesses, their families and communities. Indigenous healers and helpers can provide holistic approaches that acknowledge the interdependent relationship between mind, body, spirit and emotions from a healing and helping perspective. Complementary to Elders and Knowledge Carriers, Indigenous healers and helpers can aid in connecting or reconnecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples living with life-limiting illnesses, their families and communities to Indigenous ways of knowing, for example, end-of-life practices and ceremonies.

Navigating supports and advocating for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, particularly in rural, remote and northern communities, is critical throughout palliative and end-of-life care. The type of navigation and advocacy supports available during palliative and end-of-life care vary by jurisdiction.

Voices from the community: An Inuit lens on palliative and end-of-life care

Historically, in some Inuit communities, certain individuals were assigned the role of the messenger (Tutsalukkaijiit). Their role was to communicate the painful news of death or loss to the families when someone had died. People assigned this task had a degree of life experience and were often respected in the community. Likewise traditional health-care workers, those who tended to birth, death, or illness in communities, were persons, usually women, who had been mentored by the previous generation. Their ability to respond to the complex physical and emotional needs of families depended on what they had learned through observing and assisting the more knowledgeable mentor. Interpreters were located at a unique juncture between historical and contemporary models of care.18

Role of community leaders

Indigenous leadership at all levels in Indigenous communities is complex, intricate and multifaceted.19,20 Views of leaders and leadership have been shaped by colonization and a record of dislocation and isolation, racism, violence and poverty.21 First Nations, Inuit and Métis leaders are reminded of these events across the generations as they take on roles and responsibilities in engaging with and alongside their communities when responding to a variety of issues such as health, housing, economic diversification, education, environment, land management, children and families.22 Furthermore, they are responsible for demonstrating leadership for the roles and responsibilities of rebuilding, reuniting, reshaping and revitalizing their respective First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities while navigating intergenerational trauma often stemming from constant reminders of colonialism which includes the effects of the residential school system experience.23,24

As referenced in the complete document, Beginning the journey into the spirit world: First Nations, Inuit and Métis approaches to palliative and end-of-life care in Canada, strong local leaders in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities can serve as catalysts for transformative change in making local Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care a strategic priority as part of the continuum of care for community members across the lifespan and the generations. Such leaders are passionate, respected, influential and motivating.25

Role of families and friends

![]()

Voices from the community

“The nurses would come in to provide her with comfort medication, but it was us who had the joy and honour of caring for her, and being with her in the last hours of her life.”

My Grandma was a kind and gentle woman. She emanated that incredibly strong and silent caring of Métis women. A caring not communicated in words, but rather through action and service of her family. With absolute fondness and heart-warming feelings, I remember her laugh, her knitting, her fried bread and her quiet nature.

When she was 73, she was admitted to the hospital for an infection. During her hospital stay, she had a serious stroke which brought her to the last hours of her life.

All of my family gathered together with her that day. There was my Mom, Dad, aunts, uncles and all the cousins. There were easily 20 of us in the room with her at all times. It was a double occupancy room, but the hospital staff kindly kept the second bed unoccupied so that we could be with her in privacy. We spent the time playing cards, talking, sharing memories, laughing and just being together as a family. Grandma was in and out of consciousness, but every so often she would open her eyes just a bit and see us all there. I’m sure she could hear us. The nurses would come in to provide her with comfort medication, but it was us who had the joy and honour of caring for her, and being with her in the last hours of her life.

We were all with her when she died.

Those last moments were a celebration of her, our family, of our past, present and our future.

– Lisa Vaughn, Métis Nation of Alberta citizen

Throughout this report, there is recognition that palliative and end-of-life care supports and resources are not exclusive to people living with life-threatening illnesses but also extend to their families and communities. This includes the role of families and friends as caregivers when (i) there is a lack of access to palliative and end-of-life care and/or (ii) it is the preference of people with life-limiting illnesses for their family and/or friends to be actively involved in their palliative and end-of-life care rituals.26

The palliative and end-of-life care process can be stressful for families and friends.27,28 As a means of managing the stress surrounding illness, dying and death, Indigenous approaches to palliative and end-of-life care benefit from being guided by the roles of ancestors; community; Elders; family, friends and extended family; cultural safety; interconnectedness and relationships; diversity, self-determination and autonomy.29

Voices from the community: An Inuit lens on palliative and end-of-life care

Care providers stated that most terminally ill patients preferred to die in their homes where they are surrounded by friends, family and familiar home and community environments. Families and communities would go through great lengths to respect these wishes, often in collaboration with the local health center or regional hospitals. Families often preferred to have the patient at home for the final days of life as their own grieving process was supported when family, friends and neighbours surrounded them during the final days of a patient’s life. Women tended to be the primary caregivers for family members who are dying in the home: wives, daughters and granddaughters. Men did become involved as they may have been needed to lift or move the patient and when women were unable to provide needed care.30

In Nunavik, the definition of family is widened, creating a broader system of relations through which EOL decisions are made and caregiving responsibilities are assumed. For example, the children of nieces and nephews were also identified as one’s grandchildren and could act as key decision-makers and caregivers. Family members who had been separated by adoption as infants or youth would, at times, return and engage in providing EOL care for members of their birth family. It was not unusual for grandparents to have raised a child during formative years of that child’s life. In turn, grandchildren and great-grandchildren may have been present during the decision-making and caregiving process.31

Many Indigenous Peoples embody strength and resilience through their engagement or re-engagement in cultural and spiritual practices and an unrelenting perseverance for truth regarding the colonial history of the forced removal from traditional lands, the effects of the residential school system and cultural assimilation. Indigenous Peoples’ growing strength and resilience are resulting in calls for greater access for family and friends to visit and sit with their loved ones who have life-limiting illnesses while engaging in cultural ceremonies and practices pertaining to dying and death (for example, smudging, engaging in pipe ceremonies, preparing and sharing traditional foods, engaging in creative arts32).

1. Wildcat M, McDonald M, Irlbacher-Fox S, Coulthard G. Learning from the land: Indigenous land-based pedagogy and decolonization. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. 2014;3(3):I–XV.

2. https://soahac.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Final-V7-SOAHAC-Palliative-Care-Report-_-July-31-16.pdf

3. https://www.hospicewaterloo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Final-Report-Aboriginal-Palliative-Care-Needs-Assessment.pdf

4. Jacklin K, Warry W. Decolonizing First Nations Health. In: Kulig JC, Williams AM, editors. Health in rural Canada. Vancouver (BC): UBC Press; 2012. p. 374–375.

5. https://www.lco-cdo.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Dying-alone_An-Indigenous-mans-journey-at-EOL_C-Bablitz.pdf

6. For example, advance care planning decisions, illness progression, palliative care interventions, financial planning, assessment, decision-making and forms and equipment acquisition.

7. https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/guidelines-advice/treatment-modality/palliative-care/toolkit-aboriginal-communities

8. Hordyk SR, Macdonald ME, Brassard P. End-of-life care in Nunavik, Quebec: Inuit experiences, current realities, and ways forward. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2017;20(6):647–655.

9. Smudging involves sacred herbs burned in a shell or bowl. The smoke is brushed over the participants. It is used to purify people and places. For more information, visit

10. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/a-definition-of-smudging.

11. https://canadianaboriginal.weebly.com/rituals-worship-and-festivals.html

12. Sweat lodge ceremonies purify the body, mind, spirit and heart and restore relationships with self, others and the Creator. The sweat lodge is a sacred space. It is a closed structure with a pit where heated rocks are placed. The sweat lodge leader pours water on the hot rocks to create steam. Participants sing, pray, talk and/or meditate as they sit. For more information, visithttps://www.strongnations.com/gs/show.php?gs=4&gsd=3914.

13. Global Institute of Psychosocial, Palliative & End-of-Life Care. A search for solutions: a gathering on palliative care for First Nations, Inuit & Métis Peoples. GIPPEC Symposium Report; 2016.

14. Hordyk SR, MacDonald, ME, Brassard P. End-of-life care for Inuit living in Nunavik, Quebec: a report written for the Nunavik Regional Board of Health; 2016. p. 17.

15. Elders are First Nations, Inuit or Métis individuals who make a life commitment to the health and holistic healing of their community and Peoples.

16. Knowledge Carriers are First Nations, Inuit or Métis individuals who are recognized by their respective communities for the sharing of their culturally significant knowledge and Indigenous worldviews.

17. Healers (for example, medicine persons) often hold positions of high respect in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities.

18. Hordyk SR, MacDonald, ME, Brassard P. End-of-life care for Inuit living in Nunavik, Quebec: a report written for the Nunavik Regional Board of Health; 2016. p. 60.

19. Calliou B. The significance of building leadership and community capacity to implement self-government. In: Belanger Y, editor. Aboriginal self-government in Canada: current trends and issues. 3rd ed. Saskatoon (SK): Purich; 2008.

20. Calliou B, Voyageur C. Aboriginal leadership development: building capacity for success. Summer 2007;4:8–10.

21. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf. p. 50.

22. Sandefure G, Deloria PJ. Indigenous leadership. Daedalus. 2018;147(2):124–135.

23. https://harvest.usask.ca/bitstream/handle/10388/etd-04262005-094217/Ottmann.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

24. Wesley-Esquimaux C, Smolewski M. Historical trauma and Aboriginal healing. Ottawa (ON): Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2004.

25. Kelley M., Prince H, Nadin S, Brazil K, Crow M, Hanson G, Maki L, Monture L, Mushquash CJ, O’Brien V, Smith J. Developing palliative care programs in Indigenous communities using participatory action research: a Canadian application of the public health approach to palliative care. Annuals of Palliative Medicine. 2018;7 (Suppl2):S52–S72.

26. Kelly L, Minty, A.. End-of-life issues for Aboriginal patients: a literature review. Canadian Family Physician. 2007;53:1459–1465.

27. Gysels M, Evans N, Meñaca A, Higginson IJ, Harding R, Pool R, Project PRISMA. Diversity in defining end of life care: an obstacle or the way forward? PloS one. 2013;8(7):e68002.

28. Keeley MP. ‘Turning toward death together’: the functions of messages during final conversations in close relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24(2):225–253.

29. https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/framework-accord-cadre.pdf

30. Hordyk SR, MacDonald, ME, Brassard P. End-of-life care for Inuit living in Nunavik, Quebec: a report written for the Nunavik Regional Board of Health; 2016. p. 23.

31. Ibid. p. 23.

32. This includes, but is not limited to, writing, drawing, painting, carving, singing and dancing.