Models of Care Toolkit

- Coordination with primary care

- MODELS:

- Diagnostic pathways and rapid referral services

- Delivering culturally appropriate diagnostic care for First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples

- Connected care post-treatment

- Integrated palliative care

- Connecting patients without a primary care provider to the cancer system

Diagnostic pathways and rapid referral services

Rapid referral pathways streamline the pre-diagnosis process and improve the speed with which patients get accurate diagnoses and find cancers earlier.

Defining characteristics of a diagnostic pathway map

A – Provides a tailored snapshot of a patient’s unique care pathway.

B – Organizes information by cancer type and phase along the cancer journey

C – Designed as a tool for use by healthcare providers, administrators and people new to the cancer system.

D – Evidence-based from local, national and international clinical practice guidelines.

E – Responsive to new and rapidly evolving treatment or technology evidence.

Connected care approach

A connected care approach can support and enhance the organization of patient care through patient access to information and navigation, effective communication and cooperation across healthcare providers, as well as timely delivery of services14.

Key enablers to implementing innovative models of care in the early diagnosis phase include:

- Engagement of both cancer and primary care teams

- Leadership buy-in

- Creation of multidisciplinary teams

- Involvement of patients in planning and decision making

- A robust evaluation and sustainability plan.

The principles of equity-by-design, including goal clarity, a focus on equity-mindedness and continual learning, serve as core tenets of any major model implementation, especially those involving multiple care providers.15

Connected care approaches can also support primary care teams to play a critical role in diagnosis. Some primary care providers may face barriers such as a lack of knowledge or information to ensure patients have timely access to the right diagnostic tests16 and when to refer patients.

Although connected care models are shown to streamline the diagnosis process, the lack of patient access to primary care and the resulting reliance on walk-in clinics and emergency departments impact continuity of care and timely diagnosis.

In the Northern Zone of Nova Scotia, emergency department (ED) doctors can refer patients with a suspected cancer directly to a general practitioner in oncology (GPO) without requiring a referral from another primary care provider. GPOs either have clinic hours right in the ED or see referred patients at their own clinics.

GPOs handle comprehensive diagnostic workups and coordinate care along the correct diagnostic pathway. For patients without a primary care provider, GPOs serve as the most-responsible provider supporting more timely diagnosis.

Shelter Health Network in Hamilton, Ontario provides comprehensive care to vulnerable populations, including support for cancer diagnosis and treatment. The network uses a team-based approach to primary care for vulnerably housed people without a primary care provider. Shelter workers serve as informal navigators, helping patients move through the cancer system while addressing barriers such as transportation. By bridging gaps for patients without a primary care provider, Shelter Health Network eases pressures on local emergency departments.

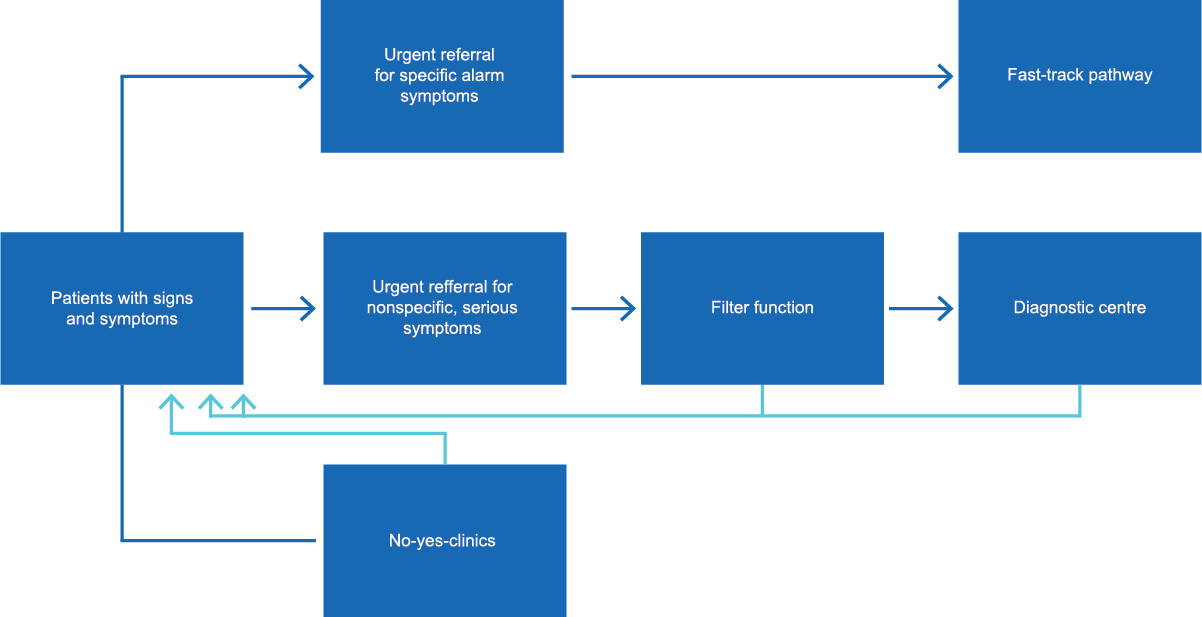

Denmark’s three-legged referral strategy provides a roadmap for primary care teams that is based on a patient’s symptoms. Recognizing each patient will present differently along the disease trajectory, the referral strategy provides a clear pathway to assess symptoms.

The three-legged referral model supports:

- Reduced wait times

- Enhanced collaboration between primary health care and cancer care

- A shift to earlier stages at diagnosis in some cancers and an increase in one-year survival rates

- Enhanced satisfaction with quality of care and wait times among patients and staff

Patients with specific alarm symptoms represent approximately half of cases and have access to an urgent referral with a 2-week wait time for a specialist based on symptom criteria listed in the pathway.

Patients with serious but unspecific symptoms represent approximately 20% of cases and have access to an urgent pathway. A family physician orders a standard battery of tests then either refers the patient to the specific urgent referral pathway or decides on further diagnostic testing.

Patients with vague and non-serious symptoms represent approximately 30% of patients. No-Yes-Clinics provide family physicians access to more detailed diagnostic investigations without referring the patient to a specialist.

The Accelerated Diagnostic Assessment Program (ADAP) at Kingston Health Sciences Centre in Ontario reduces wait-times for patients needing diagnostic workup after imaging results where cancer is suspected.

The ADAP coordinates care from referral to diagnosis and treatment. Typical ADAP patients are referred by emergency departments or primary care providers and do not meet the criteria for existing referral pathways that include potential breast, prostate, gynecologic and lung cancers.

By providing a clear pathway for primary care providers and emergency departments to refer patients with suspected cancers, the ADAP significantly shortens time for patients from referral to tissue biopsy compared to a control group and provides patients with timely access to treatment that surpasses provincial and national guidelines.

Evaluating interventions

Planning for performance measurement and evaluation early in the implementation phase supports continuous quality improvement, monitoring and learning about what’s working and why (or why not).

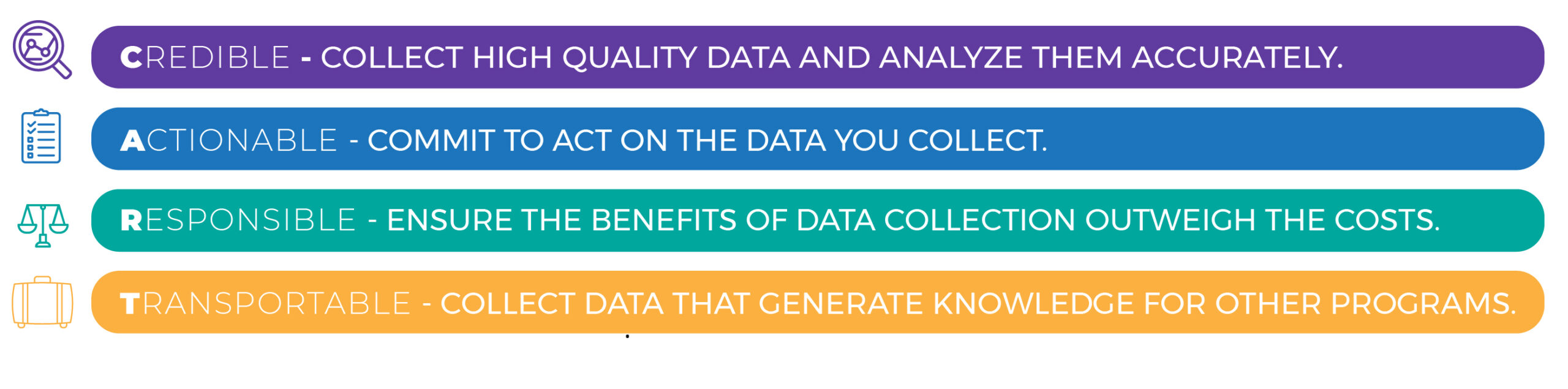

Involve key stakeholders and community partners in evaluation planning and consider applying the CART Principles to ensure the approach is credible, actionable, responsible and transportable:

Image source: Goldilocks M&E project

If an intervention is designed to address the needs of First Nations, Inuit and Métis and/or underserved communities, the project team must work with members of these communities to determine appropriate measures to describe progress and learning about advancing equity in cancer care. When implementing models for First Nations, Inuit and Métis, engage communities in model development and ensure access to culturally-appropriate diagnostic care.

Equity-based outcome indicators are critical to measuring the impact and effectiveness of such initiatives. Learn more about equity-focused evaluation and performance measurement.

- Lavis JN, Hammill AC. Care by sector. In Lavis JN (editor), Ontario’s health system: Key insights for engaged citizens, professionals and policymakers. Hamilton: McMaster Health Forum; 2016, p. 209-69.

- Tremblay D, Latreille J, Bilodeau K, et al. Improving the transition from oncology to primary care teams: A case for shared leadership. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(11):1012-1019.

- Kang J, Park EJ, Lee J. Cancer survivorship in primary care. Korean J Fam Med. 2019;40(6):353-361.

- Cancer Quality Council of Ontario. Programmatic Review on the Diagnostic Phase: Environmental Scan.; 2016.

- Gorin SS, Haggstrom D, Han PKJ, Fairfield KM, Krebs P, Clauser SB. Cancer care coordination: A systematic review and meta-analysis of over 30 years of empirical studies. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):532-546.

- Mittmann N, Beglaryan H, Liu N, et al. Examination of health system resources and costs associated with transitioning cancer survivors to primary care: A propensity-score–matched cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(11):e653-e664.

- Zhao Y, Brettle A, Qiu L. The effectiveness of shared care in cancer survivors-A systematic review. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(4):2.

- Tremblay D, Prady C, Bilodeau K, et al. Optimizing clinical and organizational practice in cancer survivor transitions between specialized oncology and primary care teams: a realist evaluation of multiple case studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1).

- Meiklejohn JA, Mimery A, Martin JH, et al. The role of the GP in follow-up cancer care: a systematic literature review. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):990-1011

- Angus Reid Institute. (2023). Health Care Access Priorities. Angus Reid Institute. Accessed December 4 2023. Available: https://angusreid.org/cma-health-care-access-priorities-2023/

- Kiran, T. (2023). Our Care National Survey. Our Care. Accessed October 13 2023. Available: https://data.ourcare.ca/all-questions.

- Watson L, Qi S, Delure A, et al. Virtual cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta: Evidence from a mixed methods evaluation and key learnings. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(9):e1354-e1361.

- Canadian Residency Matching Service. 2023 CaRMS Matching Results. Accessed December 12 2023. Available: https://www.cfpc.ca/en/education-professional-development/2023-carms-match-results.

- Walsh J, Young JM, Harrison JD, et al. What is important in cancer care coordination? A qualitative investigation: What is important in care coordination? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2011;20(2):220-227.

- Wong WF, LaVeist TA, Sharfstein JM. Achieving health equity by design. JAMA. 2015;313(14):1417-1418.

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Leading Practices to Create a Seamless Patient Experience for the Pre-Diagnosis Phase of Care: An Environmental Scan. 2018. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://canimpact.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Leading-Practices-to-Create-a-Seamless-Patient-Experience-for-the-Pre-Diagnosis-Phase-of-Care-CPAC-2018.pdf

- Cancer Council Victoria. Optimal Care Pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People with Cancer Draft for National Public Consultation.; 2017. Accessed November 22, 2021. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-09/apo-nid108366.pdf

- Jefford M, Koczwara B, Emery J, Thornton-Benko E, Vardy JL. The important role of general practice in the care of cancer survivors. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49(5):288-292.

- Healthcare Excellence Canada, the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, and Paramedics and Palliative Care teams. How Paramedics and Palliative Care contributed to better healthcare in Canada. August 2023.

- JE Terride, D Stennett, AC Coronado R Shaw Moxam, JHE Yong et al. Economic Evaluation of the “paramedics and palliative care: bringing vital services to Canadians” program compared to status quo. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2024 26: 671-680.